NOWHERE/NOW HERE THE LONG WAY BACK: WRITING THE RIDDEN WORLD #2

THE DIGITAL NOMAD EXPAT FUCKTOR

I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.”

Robert Louis Stevenson, “Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes.”

“Sometimes I wonder why we keep returning to beginnings—why we seek the single thread we might pull to unravel the tapestry we call our life in the hope that behind it we will find the truth of why.

But there is no truth. There is only why. And when we look closer we see that behind that why is just another tapestry.

And behind it another, and another, until we arrive at oblivion.”

Richard Flanagan. “Question 7.”

0. WORD OF THE WEEK: NOMAD

A nomad is, “a member of a people who have no fixed residence but move from place to place usually seasonally and within a well-defined territory.” (Merriam-Webster.)

Etymologically nomad comes from the Greek ‘Nomas,’ which means, “roaming in search of pasture.” In the 16th century the French filtered the word through their sexy phonetics, and produced “Nomade.”

Today, traditional nomads amount to 40 million people worldwide, mostly working the same pastures of their ancestors, under even more extreme weather conditions —and moving much less.

On the other hand, digital nomads have already outnumbered their traditional fellows, wandering, digitally pastoring and “peacefully” re-colonising territories unrelated to their cultural background or traditions, where they can spend most of the year blasting AC’s and in flip flops —and afford paying rent, something unconceivable at “home” for many.

1. NOWHERE, 10 THOUSAND YEARS AGO

NO-MADNESS

There was a time when you needed to be on the move in order to survive. It was way before housing, agriculture, deliveries or maps, when you had to seasonally relocate without knowing where you were heading. The paradox being that even though you were trying to survive, the reversed outcome (meaning death) was extremely high.

2. NO-MADIC

Then agriculture happened, housing bloomed, tribes settled, nomadic lifestyles diminished, and humans rewrote the terms of hunting and gathering: instead of moving chasing animals, they started moving chasing other humans and their countries, slowly forging the colonisation nightmare.

Nowadays, in alleged postcolonial times, instead of invading other humans and their countries with fire-bombers and armies, we increasingly try to buy their property first and then sublet it back to them.

It is a perfectly bloodless crime that you can typically perpetrate with just one suitcase, or a QR code —unless you have already bypassed the transactional stage thanks to your family name.

If you wish to become Italian, Portuguese or Greek, you’d ONLY need to invest 250.00€ to obtain their Golden Visa, whereas the Spaniards are currently asking for double the amount, preferably in cash.

3. DOROTHY GARROD

In 1929, the Palaeolithic archaeologist Dorothy Garrod unearthed a skull in Mount Carmel (then Palestine) that would redefine the moving narrative of mankind.

Garrod was the first archaeologist to excavate in the Middle East, where she demonstrated and coined the existence of the first sedentary, agriculture based, human society: the Natufian culture.

As Garrod’s ground-breaking findings prove, the hunter and gathering nomadic lifestyle came to a halt around twelve thousand years ago under that precise soil, a land that was yet to become the bloodiest geo-location of future mankind: Mount Carmel —then Palestine, today Israel.

Somehow, Garrod proved that in the beginning, way before the Bible or the Torah, people, cattle and nature were thriving under that soil, where the evolution of mankind reached an unparalleled, inclusive height: the Middle East became the first place on Earth were hunters and gatherers and sedentary tribes cohabited in harmony.

When families began sleeping under their own roofs, the “home” notion started to gain track. Your living room was no longer under the canopy of the stars; it was thatched and walled up, no longer public but private.

Once home-sky-watching was over, the home was slowly turned into the “private property” notion, the greediest discovery of manhood, and proverbial, muck-spreading seed of real state and nationalism, the mothers of today’s wars and banks, and two of the biggest WHYs behind the insane booming of digital nomads —and the comeback of the ugliest version of the once complimentary EXPAT word.

4. NOWHERE BETWEEN KREMLIN AND THE STARS, XMAS DAY 1991

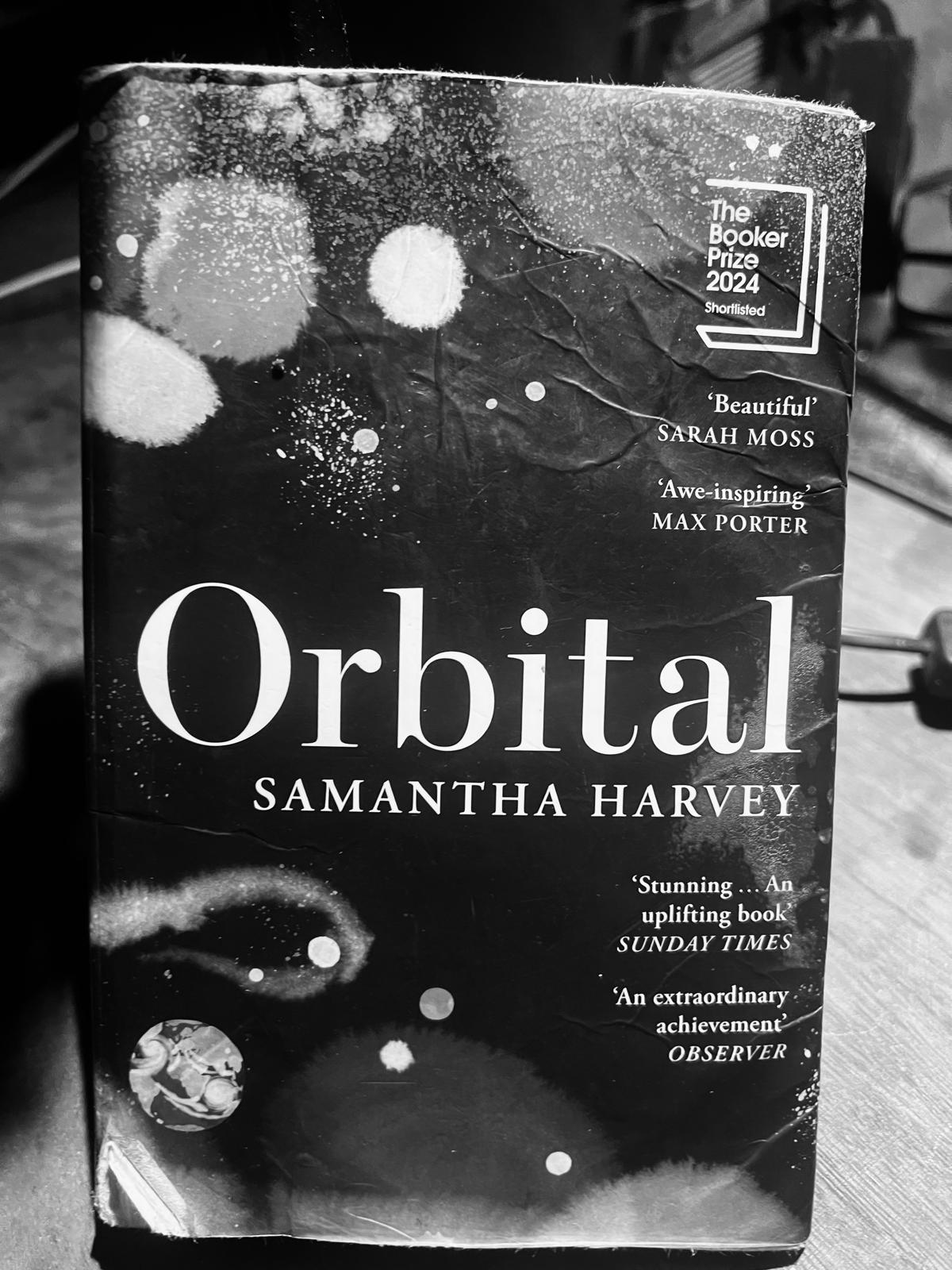

“For a split second Shaun thinks, what the hell am I doing here, in a tin can in a vacuum? A tinned man in a tin can. Four inches of titanium away from death. Not just death, obliterated non-existence.

Why would you do this? Trying to live where you can never thrive? Trying to go where the universe doesn’t want you when there’s a perfectly good earth just there that does. He’s never sure if man’s lust for space is curiosity or ingratitude. If this weird hot longing makes him a hero or an idiot. Undoubtedly something just short of either.”

—Samantha Harvey. “Orbital.”

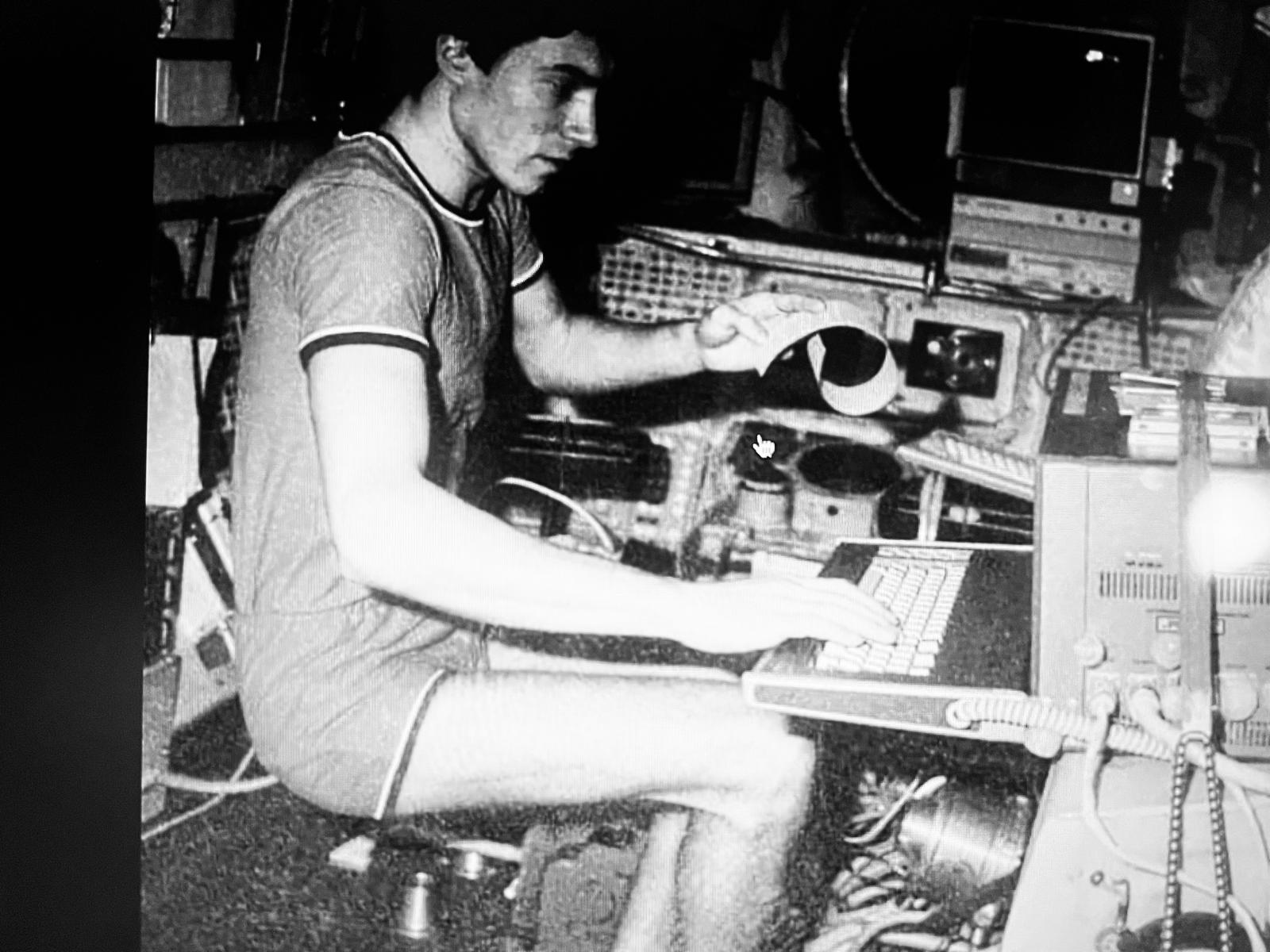

In Orbital, Samantha Harvey brilliantly recalls the story of the first digital nomad in outer space.

On Jesus’ Birthday 1991, the Soviet flag was lowered over the Kremlin for the last time. President Gorbachev resigned and next morning, on the infamous Boxing Day, the USSR collapsed.

On Jesus’ Birthday 1991, the Soviet flag was lowered over the Kremlin for the last time. President Gorbachev resigned and next morning, on the infamous Boxing Day, the USSR collapsed.

Outside the rusty and impoverished Soviet Empire, beyond Mongolia and the stratosphere, a certain Sergei Krikalev was nicknamed overnight as: “the last USSR citizen.”

He was at an astronaut at work at the MIR space station, ready to come back to Earth, when the news about the geophysical disintegration of his homeland broke.

Harvey writes that shortly after finding out that he was to remain orbiting the Earth for an unknown amount of time, “Every day for a year Krikalev talked with a Cuban woman by packet radio who sent him news of his collapsing country.”

Upon finding out the disturbing news, Sergei Krikalev looked out the window as if it were possible to see from his locked frame the political rearrangement that a vast territory of the blue Earth was undergoing.

The end of his home notion turned him into the first unsolicited digital nomad to ever orbit the planet, setting the cornerstone of his future world record: today he is celebrated as the most experienced astronaut ever, having spent a cumulative total of 803 days beyond the oceans and the stars.

PLURAL DEMISE

Back in 1991 though, Sergei had no world records in mind, but serious concerns about becoming the first man to die alone in space. He feared that he could be deserted and let adrift by his dilapidated country, and was also very much aware that if he were to be neglected, his worst outcome was known as “spaghettification,” which is what Matthew McConaughey’s character dodges in Interstellar, the process where a body is stretched vertically and squeezed horizontally due to immense tidal forces in a strong gravitational field, typically a black hole.

If any of us is to enter such unfathomable darkness our bodies will stretch and narrow until turning us into… well, human spaghetti.

Not bad, but far from ideal.

5. THE FUTURE IS HERE

Within the next decade, for the first time in 10,000 years, most people will find that the geographic tie is dissolving. It will happen gradually and people will be slow to realise that a revolution is occurring but, by the end of those ten years, most people in the developed world will find themselves free to live where they want and travel as much as they want. The 21st century will be the millennium which resurrects for humans a dilemma which has been dormant for 10,000 years—humans will be able to ask themselves: ‘Am I a Nomad or a Settler?’

Tsugio Makimoto, David Manners. “Digital Nomad.”

In 1997, Tsugio Makimoto and David Manners wrote a seminal and quite accurate essay predicting the imminent emergence of a new phenomenon in the labour market: working remotely.

Makimoto and Manners coined the DM term, and foresaw that in the following decades the number of people moving abroad to work online would redefine the terms of nomadism, an ancient way of living that technologies were about to revive, therefore their question: “Am I a Nomad or a Settler?”

Almost three decades later, their prophetic forecast has boomed beyond imagined numbers, but what they couldn’t possibly foresee was that digital nomadism would bring back to life a noun that had been morbidly dying for decades: “expat.”

6. THE EXPAT FUCKTOR

If you were to break down the etymology of all the terms related to traveling, not many would score as low as expat. “To banish, send out of one’s native country.”

Except back in the day, during the previous life of the said word, to be banished was almost a compliment to your virtue: either you were graciously gifted at breaking down the wrongdoings of your home country; or you excelled at strangulate them with your own hands.

7. GET THE FUCK OUT

When you spend your (de) formative years in the same place, the inescapable ‘home’, you become inextricably intertwined with its fabric.

You don’t get to choose your cultural background or upbringing; you just suck it all up, half by osmosis, half by inevitable exposure to things that you have not chosen to live or understand.

By the time you finally reach discernment and become your own person, the whole mind-fuck is part of you, and no matter how good you might be at shattering it, your chances of attaining freedom will depend on how good you are at absconding your indoctrinated cage —if you are lucky enough not to have been brainwashed beyond redemption.

Somehow, home is the bureau of all your classified, biased and prejudiced perception of reality. Can you crack that up and find a way out?

8. CAGED

Expats are proficient at avoiding harsh weathers and at finding very reasonable housing far from home, and their main existential issue is rather semantic: many collapse after a while upon realising that they will never be able to escape the expat-word-cage.

Maggie Nelson argues in her unkempt memorable book, “The Argonauts” that the Zen master musician John Cage spent most of his life trying to escape his tricky name:

“In response to a journalist who asked him to “summarize himself in a nutshell,” John Cage once said, ‘Get yourself out of whatever cage you find yourself in.’ He knew his name was stuck to him, or he was stuck to it. ”

—Maggie Nelson. “The Argonauts.”

9. DETTACHED KINGDOM

You first escape home and then escape the global asphyxiation —but not the expat cage.

“In completely disparate circles—such as those of leftist political philosophy, for example—a distinct but not wholly unrelated idea of “engaged withdrawal” has also begun to hold sway. Rather than fixate on revolution, this strategy privileges orchestrated and unorchestrated acts of exodus… ephemeral but crucial gaps in an otherwise suffocating global capitalist order, gaps that, at the very least, make other forms of social organization and perception seem momentarily possible.”

Maggie Nelson. “The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning.”

At this point of boiling gentrification, both East and West are possessed by the same flash-judging morals of antediluvian humanity, despising or accepting people based on their haircut, accent, clothes or even shopping bags —let alone social media profiles and nationality.

Today’s expats are mostly digital, free-willing nomads that can improve their own lives at the risk of triggering vertiginous rises in the price of living of their invaded places of choice.

Barcelona, Lisbon, Dublin or Mexico City are leading a race that will spread like wildfire in no time: to push away their locals by blowing up their rents and selling their homes to those who can afford them, preferably in cash.

As of today there are already almost 65 million digital nomads blinking worldwide, and estimations predict that they will be one billion by 2035.

Can you picture “home” in ten years?

Think out of the box —or the cage.

Or perhaps don’t think and live?